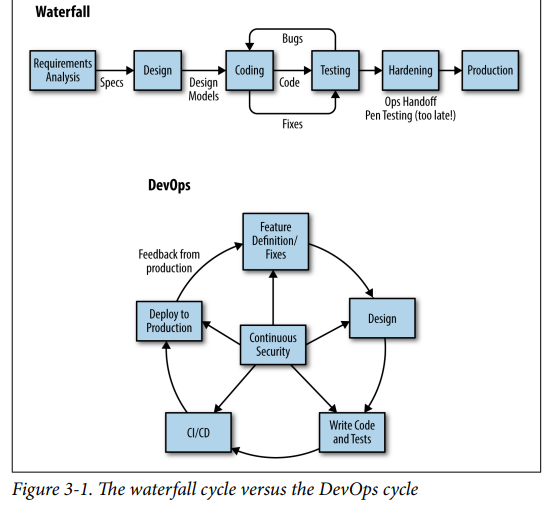

Instead of trying to plan and design everything upfront, DevOps organizations are running continuous experiments and using data from these experiments to drive design and process improvements.

- taking advantage of new tools such as programmable con‐ figuration managers and application release automation to simplify and scale everything from design to build and deployment and operations, and taking advantage of cloud services, virtualization, and containers to spin up and run systems faster and cheaper.

DevOps:

Infrastructure as Code: * Chef ,puppet terraform these softwares are increase speed of building systems and scaling them. * full visibility into configuration details, control over configuration drift and elimination of one-off snowflakes, and a way to define and automatically enforce security policies at run‐ time.

Continuous Delivery:

Continuous monitoring and measurement This involves creating feedback loops from production back to engineering, collecting metrics, and making them visible to everyone to understand how the system is actually used and using this data to learn and improve. You can extend this to security to provide insight into security threats and enable “Attack-Driven Defense.”

Learning From Failure

- chaos engineering, and practicing for failure in game days.

Amazon has thousands of small (“two pizza”) engineering teams working inde‐ pendently and continuously deploying changes across their infra‐ structure. In 2014, Amazon deployed 50 million changes: that’s more than one change deployed every second of every day.1 So much change so fast… How can security possibly keep up with this rate of change?

DevOps is heavily influenced by Lean principles: maximizing effi‐ ciency and eliminating waste and delays and unnecessary costs.

Major security risks facing users of cloud computing services:

- Data breaches

- Weak identity, credential, and access management

- Insecure interfaces and APIs

- System and application vulnerabilities

- Account hijacking

- Malicious insiders

- Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs)

- Data loss

- Insufficient due diligence

- Abuse and nefarious use of cloud services

- Denial of Service

- Shared technology issues

microservice An individual microservice fits in your head, but the interrelationships among them exceed any human’s understanding

Attack surface. The attack surface of any microservice might be tiny, but the total attack surface of the system can be enormous and hard to see.

Unlike a tiered web application, there is no clear perimeter, no obvious “choke points” where you can enforce authentication or access control rules. You need to make sure that trust bound‐ aries are established and consistently enforced.

The polyglot programming problem. If each team is free to use what they feel are the right tools for the job (like at Amazon), it can become extremely hard to understand and manage security risks across many different languages and frameworks.

Logging strategy, forensics and auditing across different services with different logging approaches can be a nightmare.

Docker Security Risks

- Kernel exploits

- DOS attacks one container can monopolize access to certain resources–including memory and more esoteric resources such as user IDs (UIDs)—it can starve out other containers on the host, resulting in a denial-of-service (DoS), whereby legitimate users are unable to access part or all of the system.

- Container breakouts

users are not namespaced, so any process that breaks out of the container will have the same privileges on the host as it did in the container; if you were

rootin the container, you will berooton the host. - Poisoned Images

- Compromising Secrets

Docker Bench Security #todos We can automatize this process when we use docker pull or etc. You can lock down a container by using CIS guidelines and other security best practices and using scanning tools like Docker Bench, and you can minimize the container’s attack surface by stripping down the runtime dependencies and making sure that developers don’t package up development tools in a production container. But all of this requires extra work and knowing what to do.

Etys’s DevSecOps

- Trust people to do the right thing, but still verify. Rely on code reviews and testing and secure defaults and training to prevent or catch mistakes

- If it Moves, Graph it.” Make data visible to everyone so that everyone can understand and act on it, including information about security risks, threats, and attacks. Data visulations

- “Just Ship It.” Every engineer can push to production at any time. This includes security engineers. If something is broken 17 1 Rich Smith, Director of Security Engineering, Etsy. “Crafting an Effective Security Organization.” QCon 2015 http://www.infoq.com/presentations/security-etsy and you can fix it, fix it and ship the fix out right away

- Understand the real risk to the system and to the organization and deal with problems appropriately.

“Designated Hackers” is a system by which each security engineer supports four or five development teams across the organization and are involved in design and standups.

THIS CALL AS Shifting Security Left

and how to take advantage of security features in their application frameworks and security libraries to prevent common security vulnerabilities like injection attacks. The OWASP and SAFECode communities provide a lot of useful, free tools and frameworks and guidance to help developers with understanding and solving common application security problems in any kind of system.

THIS CALL AS Shifting Security Left

and how to take advantage of security features in their application frameworks and security libraries to prevent common security vulnerabilities like injection attacks. The OWASP and SAFECode communities provide a lot of useful, free tools and frameworks and guidance to help developers with understanding and solving common application security problems in any kind of system.

OWASP Proactive Control

- Verify for security early and often

- parametrize queries ⇒ Prevent SQL injection by using a parameterized database inter‐ face.

- encode data

- Validate all inputs

- Implement identity and authentication controls

- Implement appropriate access controls

- Protect data

- Implement logging and intrusion detection

- Take advantage of security frameworks and libraries

- Error and exception handling

CANARY RELEASING Another way to minimize the risk of change in Continuous Delivery or Continuous Deployment is canary releasing. Changes can be rol‐ led out to a single node first, and automatically checked to ensure that there are no errors or negative trends in key metrics (for exam‐ ple, conversion rates), based on “the canary in a coal mine” meta‐ phor. If problems are found with the canary system, the change is rolled back, the deployment is canceled, and the pipeline shut down until a fix is ready to go out. After a specified period of time, if the canary is still healthy, the changes are rolled out to more servers, and then eventually to the entire environment.s

Honeymoon Effect older software that is more vulnerable is easier to attack than software that has recently been changed. Attacks take time. It takes time to identify vulnerabilities, time to understand them, and time to craft and execute an exploit. This is why many attacks are made against legacy code with known vulner‐ abilities. In an environment where code and configuration changes are rolled out quickly and changed often, it is more difficult for attackers to follow what is going on, to identify a weakness, and to understand how to exploit it. The system becomes a moving target. By the time attackers are ready to make their move, the code or con‐ figuration might have already been changed and the vulnerability might have been moved or closed

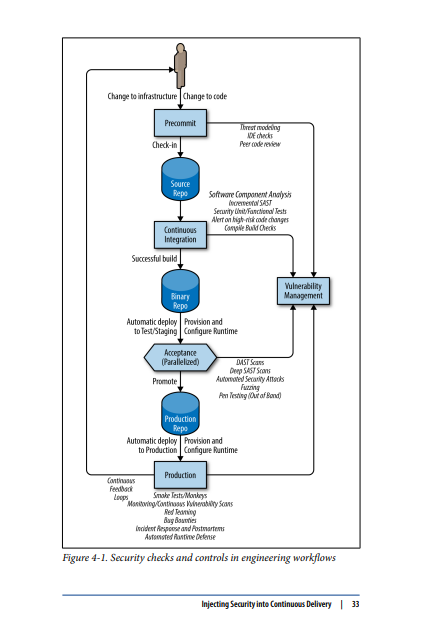

Continuous Delivery is provisioning and configuring test environ‐ ments to match production as closely as possible—automatically.This includes packaging the code and deploying it to test environ‐ ments; running acceptance, stress, and performance tests, as well as security tests and other checks, with pass/fail feedback to the team, all automatically; and auditing all of these steps and communicating status to a dashboard.Later, you use the same pipeline to deploy the changes to production.

Injecting Security into Continuous Delivery

Ask these questions before you start:

What happens before and when a change is checked in? • Where are the repositories? Who has access to them? • How do changes transition from check-in to build to Continu‐ ous Integration and unit testing, to functional and integration testing, and to staging and then finally to production? • What tests are run? Where are the results logged? • What tools are used? How do they work? • What manual checks or reviews are performed and when?

Precommit

lightweight iterative threat modeling and risk assesments SAST (Static Analysis) checking in engineers IDE Peer code reviews ( for defensive coding and security vulnerabilities)

Commit Stage (Continuos Integration)

This is automatically triggered by a check in. In this stage, you build and perform basic automated testing of the system. These steps return fast feedback to developers: did this change “break the build”?

security checks that you should include in this stage:

• Compile and build checks, ensuring that these steps are clean, and that there are no errors or warnings

- Software Component Analysis in build, identifying risk in thirdparty components

- Incremental static analysis scanning for bugs and security vul‐ nerabilities

- • Alerting on high-risk code changes through static analysis checks or tests

-

- Automated unit testing of security functions, with code cover‐ age analysis

- Digitally signing binary artifacts and storing them in secure repositories (For software that is distributed externally, this should involve signing the code with a code-signing certificate from a third-party CA. For internal code, a hash should be enough to ensure code integrity.)

Acceptance Stage

To minimize the time required, these tests are often fanned out to different test servers and executed in parallel. Following a “fail fast” approach, the more expensive and time-consuming tests are left until as late as possible in the test cycle, so that they are only executed if other tests have already passed.

• Secure, automated configuration management and provisioning of the runtime environment (using tools like Ansible, Chef, Puppet, Salt, and/or Docker). Ensure that the test environment is clean and configured to match production as closely as possi‐ ble.

• Automatically deploy the latest good build from the binary arti‐ fact repository.

• Smoke tests (including security tests) designed to catch mistakes in configuration or deployment.

• Targeted dynamic scanning (DAST).

• Automated functional and integration testing of security fea‐ tures.

• Automated security attacks, using Gauntlt or other security tools. • Deep static analysis scanning (can be done out of band).

•Fuzzing (of APIs, files). This can be done out of band.

• Manual pen testing (out of band).

Production Deployment and Post-Deployment

ending manual review/approvals and scheduling (in Continuous Delivery) or automatically (in Continu‐ ous Deployment).

- Secure automated configuration managment and provisiong of runtime env

- Automated deployment and release orchestration

- Post-Deployment smoke test

- Automated runtime asserts and compliance checks (monkeys)

- Production monitoring/feedback

- Runtime defense

- Red teaming

- Bug bounties

- Blameless postmortems (learning from failure)

Source code

Luckily, you can do this automatically by using Software Compo‐ nent Analysis (SCA) tools like OWASP’s Dependency Check project or commercial tools like Sonatype’s Nexus Lifecycle or SourceClear.

OWASP’s Dependency Check is an open source scanner that cata‐ logs open source components used in an application. It works for Java, .NET, Ruby (gemspec), PHP (composer), Node.js and Python, and some C/C++ projects. Dependency Check integrates with com‐ mon build tools (including Ant, Maven, and Gradle) and CI servers like Jenkins.

Code reviews tools needs to invatigate.

You should not rely on only one tool—even the best tools will catch only some of the problems in your code. Good practice would be to run at least one of each kind to look for different problems in the code, as part of an overall code quality and security program.

You can use tools like OWASP ZAP to automatically scan a web app for common vulnerabilities as part of the Continuous Integration/ Continuous Delivery pipeline. You can do this by running the scan‐ ner in headless mode through the command line, through the scan‐ ner’s API, or by using a wrapper of some kind, such as the ZAProxy Jenkins plug-in or a higher-level test framework like BDD-Security (which we’ll look at in a later section)

fuzzing Some newer fuzzing tools are designed to run (or can be adapted to run) in Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery. They let you to seed test values to create repeatable tests, set time boxes on test runs, detect duplicate errors, and write scripts to automatically set up/restore state in case the system crashes. But you might still find that fuzz testing is best done out of band.

Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) and TestDriven Development (TDD)—wherein developers write tests before they write the code—encourage developers to create a strong set of automated tests to catch mistakes and protect themselves from regressions as they add new features or make changes or fixes to the code

Automated Attacks

Tools for automated attacks

• Gauntlt • Mittn • BDD-Security

Vulnerability Management

- How many vulnerabilities have you found? • How were they found? What tools or testing approaches are giv‐ ing you the best returns? • What are the most serious vulnerabilities? • How long are they taking to get fixed? Is this getting better or worse over time?

Continuous Delivery pipelines into a vulnerability manager, such as Code Dx or ThreadFix.

Continuous Delivery pipeline: • Harden the systems that host the source and build artifact repo‐ sitories, the Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery server(s), and the systems that host the configuration manage‐ ment, build, deployment, and release tools. Ensure that you clearly understand—and control—what is done on-premises and what is in the cloud. • Harden the Continuous Integration and/or Continuous Deliv‐ ery server. Tools like Jenkins are designed for developer conve‐ nience and are not secure by default. Ensure that these tools (and the required plug-ins) are kept up-to-date and tested fre‐ quently. • Lock down and harden your configuration management tools. See “How to be a Secure Chef,” for example. • Ensure that keys, credentials, and other secrets are protected. Get secrets out of scripts and source code and plain-text files and use an audited, secure secrets manager like Chef Vault, Square’s KeyWhiz project, or HashiCorp Vault. • Secure access to the source and binary repos and audit access to them. • Implement access control across the entire tool chain. Do not allow anonymous or shared access to the repos, to the Continu‐ ous Integration server, or confirmation manager or any other tools. • Change the build steps to sign binaries and other build artifacts to prevent tampering. • Periodically review the logs to ensure that they are complete and that you can trace a change through from start to finish. Ensure that the logs are immutable, that they cannot be erased or forged. • Ensure that all of these systems are monitored as part of the production environment.

Runtime Application Security Protection/Self-Protection (RASP) which uses run-time instrumentation to catch security problems as they occur. Like application firewalls, RASP can automatically identify and block attacks. And like application firewalls, you can extend RASP to leg‐ acy apps for which you don’t have source code.

There are only a small number of RASP solutions available today, mostly limited to applications that run in the Java JVM and .NET CLR, although support for other languages like Node.js, Python, and Ruby is emerging. These tools include the following:

• Immunio • Waratek • Prevoty