comments: true

Code and Project Organization

Unintended variable shadowing (#1)

info “TL;DR”

Avoiding shadowed variables can help prevent mistakes like referencing the wrong variable or confusing readers.

Variable shadowing occurs when a variable name is re-declared in an inner block, but this practice is prone to mistakes. Imposing a rule to forbid shadowed variables depends on personal taste. For example, sometimes it can be convenient to reuse an existing variable name like err for errors. Yet, in general, we should remain cautious because we now know that we can face a scenario where the code compiles, but the variable that receives the value is not the one expected.

Unnecessary nested code (#2)

info “TL;DR”

Avoiding nested levels and keeping the happy path aligned on the left makes building a mental code model easier.

In general, the more nested levels a function requires, the more complex it is to read and understand. Let’s see some different applications of this rule to optimize our code for readability:

- When an

ifblock returns, we should omit theelseblock in all cases. For example, we shouldn’t write:

if foo() {

// ...

return true

} else {

// ...

}Instead, we omit the else block like this:

if foo() {

// ...

return true

}

// ...- We can also follow this logic with a non-happy path:

if s != "" {

// ...

} else {

return errors.New("empty string")

}Here, an empty s represents the non-happy path. Hence, we should flip the

condition like so:

if s == "" {

return errors.New("empty string")

}

// ...Writing readable code is an important challenge for every developer. Striving to reduce the number of nested blocks, aligning the happy path on the left, and returning as early as possible are concrete means to improve our code’s readability.

Misusing init functions (#3)

info “TL;DR”

When initializing variables, remember that init functions have limited error handling and make state handling and testing more complex. In most cases, initializations should be handled as specific functions.

An init function is a function used to initialize the state of an application. It takes no arguments and returns no result (a func() function). When a package is initialized, all the constant and variable declarations in the package are evaluated. Then, the init functions are executed.

Init functions can lead to some issues:

- They can limit error management.

- They can complicate how to implement tests (for example, an external dependency must be set up, which may not be necessary for the scope of unit tests).

- If the initialization requires us to set a state, that has to be done through global variables.

We should be cautious with init functions. They can be helpful in some situations, however, such as defining static configuration. Otherwise, and in most cases, we should handle initializations through ad hoc functions.

package main

import (

"database/sql"

"log"

"os"

)

var db *sql.DB

func init() {

dataSourceName := os.Getenv("MYSQL_DATA_SOURCE_NAME")

d, err := sql.Open("mysql", dataSourceName)

if err != nil {

log.Panic(err)

}

err = d.Ping()

if err != nil {

log.Panic(err)

}

db = d

}

func createClient(dataSourceName string) (*sql.DB, error) {

db, err := sql.Open("mysql", dataSourceName)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if err = db.Ping(); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return db, nil

}Golang ad hoc functions

In Go (Golang), the concept of ad hoc functions can be illustrated through the use of function literals (also known as anonymous functions) or specifically tailored named functions for certain tasks. Let's see how this contrasts with the use of `init` functions.

1. **Using `init` Function**:

The `init` function in Go is a special function that is automatically executed when a package is initialized. It's often used for setup tasks like initializing global variables or configuration settings.

```go

package mypackage

var globalConfig Config

func init() {

globalConfig = LoadConfig("config.json")

}-

Using Ad Hoc Functions for Initialization: Instead of relying on

init, you can create ad hoc functions for initialization. This approach gives you more control over when and how initialization happens, especially if the initialization process is context-specific.package mypackage var globalConfig Config // LoadConfiguration is an ad hoc function for initializing the config func LoadConfiguration(path string) { globalConfig = LoadConfig(path) } // This function can be called explicitly at the start of your main function or wherever it's needed func main() { mypackage.LoadConfiguration("config.json") // Rest of your main function }

In this example, instead of using an init function which runs automatically and can sometimes lead to less predictable behavior or initialization order issues, you explicitly call LoadConfiguration in your main function or wherever appropriate. This approach provides clearer control over the initialization process, making the code more understandable and maintainable.

Overusing getters and setters (#4)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Forcing the use of getters and setters isn’t idiomatic in Go. Being pragmatic and finding the right balance between efficiency and blindly following certain idioms should be the way to go.

Data encapsulation refers to hiding the values or state of an object. Getters and setters are means to enable encapsulation by providing exported methods on top of unexported object fields.

In Go, there is no automatic support for getters and setters as we see in some languages. It is also considered neither mandatory nor idiomatic to use getters and setters to access struct fields. We shouldn’t overwhelm our code with getters and setters on structs if they don’t bring any value. We should be pragmatic and strive to find the right balance between efficiency and following idioms that are sometimes considered indisputable in other programming paradigms.

Remember that Go is a unique language designed for many characteristics, including simplicity. However, if we find a need for getters and setters or, as mentioned, foresee a future need while guaranteeing forward compatibility, there’s nothing wrong with using them.

Interface pollution (#5)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Abstractions should be discovered, not created. To prevent unnecessary complexity, create an interface when you need it and not when you foresee needing it, or if you can at least prove the abstraction to be a valid one.

An interface provides a way to specify the behavior of an object. We use interfaces to create common abstractions that multiple objects can implement. What makes Go interfaces so different is that they are satisfied implicitly. There is no explicit keyword like implements to mark that an object X implements interface Y.

In general, we can define three main use cases where interfaces are generally considered as bringing value: factoring out a common behavior, creating some decoupling, and restricting a type to a certain behavior. Yet, this list isn’t exhaustive and will also depend on the context we face.

In many occasions, interfaces are made to create abstractions. And the main caveat when programming meets abstractions is remembering that abstractions should be discovered, not created. What does this mean? It means we shouldn’t start creating abstractions in our code if there is no immediate reason to do so. We shouldn’t design with interfaces but wait for a concrete need. Said differently, we should create an interface when we need it, not when we foresee that we could need it. What’s the main problem** if we overuse interfaces? The answer is that they make the code flow more complex.**** Adding a useless level of indirection doesn’t bring any value**; it creates a worthless abstraction making the code more difficult to read, understand, and reason about. If we don’t have a strong reason for adding an interface and it’s unclear how an interface makes a code better, we should challenge this interface’s purpose. Why not call the implementation directly?

We should be cautious when creating abstractions in our code (abstractions should be discovered, not created). It’s common for us, software developers, to overengineer our code by trying to guess what the perfect level of abstraction is, based on what we think we might need later. This process should be avoided because, in most cases, it pollutes our code with unnecessary abstractions, making it more complex to read.

!!! quote “Rob Pike”

Don’t design with interfaces, discover them.

Let’s not try to solve a problem abstractly but solve what has to be solved now. Last, but not least, if it’s unclear how an interface makes the code better, we should probably consider removing it to make our code simpler.

//with decoupling

package main

import "fmt"

// Customer represents a customer with an ID

type Customer struct {

id string

}

// customerStorer is an interface for storing customers

type customerStorer interface {

StoreCustomer(Customer) error

}

// CustomerService2 holds a storer that conforms to the customerStorer interface

type CustomerService2 struct {

storer customerStorer

}

// CreateNewCustomer creates a new customer and stores it using the storer in CustomerService2

func (cs *CustomerService2) CreateNewCustomer(id string) error {

customer := Customer{id: id}

return cs.storer.StoreCustomer(customer)

}

// mockCustomerStorer is a mock implementation of the customerStorer interface

type mockCustomerStorer struct{}

// StoreCustomer is a mock method to store a customer

func (m *mockCustomerStorer) StoreCustomer(c Customer) error {

// Mock storing the customer, in real implementation this might interact with a database

fmt.Printf("Storing customer with id: %s\n", c.id)

return nil

}

func main() {

// Create a CustomerService2 with a mockCustomerStorer

service := CustomerService2{storer: &mockCustomerStorer{}}

// Create a new customer

err := service.CreateNewCustomer("123")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error creating customer:", err)

}

}

Interface on the producer side (#6)

info “TL;DR”

Keeping interfaces on the client side avoids unnecessary abstractions.

Interfaces are satisfied implicitly in Go, which tends to be a gamechanger compared to languages with an explicit implementation. In most cases, the approach to follow is similar to what we described in the previous section: abstractions should be discovered, not created. This means that it’s not up to the producer to force a given abstraction for all the clients. Instead, it’s up to the client to decide whether it needs some form of abstraction and then determine the best abstraction level for its needs.

An interface should live on the consumer side in most cases. However, in particular contexts (for example, when we know—not foresee—that an abstraction will be helpful for consumers), we may want to have it on the producer side. If we do, we should strive to keep it as minimal as possible, increasing its reusability potential and making it more easily composable.

package main

import "fmt"

// SimpleLogger is defined by the client who needs only basic logging

type SimpleLogger interface {

Log(message string)

}

// VerboseLogger is defined by another client who needs detailed logging

type VerboseLogger interface {

Log(message string)

LogDetail(detail string)

}

// ConsoleLogger is a producer that implements both methods

type ConsoleLogger struct{}

func (l ConsoleLogger) Log(message string) {

fmt.Println("Log:", message)

}

func (l ConsoleLogger) LogDetail(detail string) {

fmt.Println("Detail:", detail)

}

func performLogging(l SimpleLogger) {

l.Log("Simple logging")

}

func performDetailedLogging(l VerboseLogger) {

l.Log("Verbose logging")

l.LogDetail("Detailed information")

}

func main() {

logger := ConsoleLogger{}

// Using logger where a SimpleLogger is needed

performLogging(logger)

// Using logger where a VerboseLogger is needed

performDetailedLogging(logger)

}

Returning interfaces (#7)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To prevent being restricted in terms of flexibility, a function shouldn’t return interfaces but concrete implementations in most cases. Conversely, a function should accept interfaces whenever possible.

In most cases, we shouldn’t return interfaces but concrete implementations. Otherwise, it can make our design more complex due to package dependencies and can restrict flexibility because all the clients would have to rely on the same abstraction. Again, the conclusion is similar to the previous sections: **if we know (not foresee) that an abstraction will be helpful for clients, we can consider returning an interface. Otherwise, we shouldn’t force abstractions; they should be discovered by clients. **If a client needs to abstract an implementation for whatever reason, it can still do that on the client’s side.

any says nothing (#8)

info “TL;DR”

Only use `any` if you need to accept or return any possible type, such as `json.Marshal`. Otherwise, `any` doesn’t provide meaningful information and can lead to compile-time issues by allowing a caller to call methods with any data type.

The any type can be helpful if there is a genuine need for accepting or returning any possible type (for instance, when it comes to marshaling or formatting). In general, we should avoid overgeneralizing the code we write at all costs. Perhaps a little bit of duplicated code might occasionally be better if it improves other aspects such as code expressiveness.

Being confused about when to use generics (#9)

info “TL;DR”

Relying on generics and type parameters can prevent writing boilerplate code to factor out elements or behaviors. However, do not use type parameters prematurely, but only when you see a concrete need for them. Otherwise, they introduce unnecessary abstractions and complexity.

Read the full section here.

Notes about ~

In Go, the ~ symbol is used in type constraints (introduced in Go 1.18 with the addition of Generics) to denote type identity. Specifically, when used in a type constraint, ~T means “any type that is identical to T”. This is a way to specify that a type argument must be exactly T, or a type defined as a type alias of T.

In your example:

type customConstraint interface {

~int | ~string

}This is defining a type constraint customConstraint that allows any type that is either identical to int or string. Here, “identical” means the type itself or any type that is defined as a type alias of int or string.

To clarify:

~intallowsintand any type that is a type alias ofint.~stringallowsstringand any type that is a type alias ofstring.

The | symbol in the constraint represents a union, meaning that the type can be either one of those specified.

This constraint can be used in a generic function or type. For instance, a generic function that accepts arguments of types satisfying customConstraint could accept both int and string types, as well as any types aliased to int or string.

Here’s an example of how you might use this constraint:

package main

import "fmt"

type customConstraint interface {

~int | ~string

}

func Print[T customConstraint](value T) {

fmt.Println(value)

}

func main() {

Print(123) // int

Print("abc") // string

type MyInt int

type MyString string

Print(MyInt(456)) // MyInt, an alias of int

Print(MyString("def")) // MyString, an alias of string

}In this example, Print is a generic function that can accept arguments of either int, string, or any types aliased to int or string due to the customConstraint interface.

Not being aware of the possible problems with type embedding (#10)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using type embedding can also help avoid boilerplate code; however, ensure that doing so doesn’t lead to visibility issues where some fields should have remained hidden.

When creating a struct, Go offers the option to embed types. But this can sometimes lead to unexpected behaviors if we don’t understand all the implications of type embedding. Throughout this section, we look at how to embed types, what these bring, and the possible issues.

In Go, a struct field is called embedded if it’s declared without a name. For example,

type Foo struct {

Bar // Embedded field

}

type Bar struct {

Baz int

}In the Foo struct, the Bar type is declared without an associated name; hence, it’s an embedded field.

We use embedding to promote the fields and methods of an embedded type. Because Bar contains a Baz field, this field is

promoted to Foo. Therefore, Baz becomes available from Foo.

What can we say about type embedding? First, let’s note that it’s rarely a necessity, and it means that whatever the use case, we can probably solve it as well without type embedding. Type embedding is mainly used for convenience: in most cases, to promote behaviors.

If we decide to use type embedding, we need to keep two main constraints in mind:

- It shouldn’t be used solely as some syntactic sugar to simplify accessing a field (such as

Foo.Baz()instead ofFoo.Bar.Baz()). If this is the only rationale, let’s not embed the inner type and use a field instead. - It shouldn’t promote data (fields) or a behavior (methods) we want to hide from the outside: for example, if it allows clients to access a locking behavior that should remain private to the struct.

Using type embedding consciously by keeping these constraints in mind can help avoid boilerplate code with additional forwarding methods. However, let’s make sure we don’t do it solely for cosmetics and not promote elements that should remain hidden.

Not using the functional options pattern (#11)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To handle options conveniently and in an API-friendly manner, use the functional options pattern.

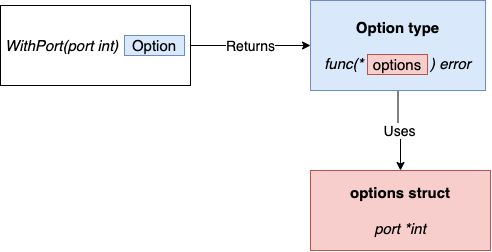

Although there are different implementations with minor variations, the main idea is as follows:

- An unexported struct holds the configuration: options.

- Each option is a function that returns the same type:

type Option func(options *options)error. For example,WithPortaccepts anintargument that represents the port and returns anOptiontype that represents how to update theoptionsstruct.

type options struct {

port *int

}

type Option func(options *options) error

func WithPort(port int) Option {

return func(options *options) error {

if port < 0 {

return errors.New("port should be positive")

}

options.port = &port

return nil

}

}

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...Option) ( *http.Server, error) { <1>

var options options <2>

for _, opt := range opts { <3>

err := opt(&options) <4>

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

// At this stage, the options struct is built and contains the config

// Therefore, we can implement our logic related to port configuration

var port int

if options.port == nil {

port = defaultHTTPPort

} else {

if *options.port == 0 {

port = randomPort()

} else {

port = *options.port

}

}

// ...

}The functional options pattern provides a handy and API-friendly way to handle options. Although the builder pattern can be a valid option, it has some minor downsides (having to pass a config struct that can be empty or a less handy way to handle error management) that tend to make the functional options pattern the idiomatic way to deal with these kind of problems in Go.

Project misorganization (project structure and package organization) (#12)

Regarding the overall organization, there are different schools of thought. For example, should we organize our application by context or by layer? It depends on our preferences. We may favor grouping code per context (such as the customer context, the contract context, etc.), or we may favor following hexagonal architecture principles and group per technical layer. If the decision we make fits our use case, it cannot be a wrong decision, as long as we remain consistent with it.

Regarding packages, there are multiple best practices that we should follow. First, we should avoid premature packaging because it might cause us to overcomplicate a project. Sometimes, it’s better to use a simple organization and have our project evolve when we understand what it contains rather than forcing ourselves to make the perfect structure up front. Granularity is another essential thing to consider. We should avoid having dozens of nano packages containing only one or two files. If we do, it’s because we have probably missed some logical connections across these packages, making our project harder for readers to understand. Conversely, we should also avoid huge packages that dilute the meaning of a package name.

Package naming should also be considered with care. As we all know (as developers), naming is hard. To help clients understand a Go project, we should name our packages after what they provide, not what they contain. Also, naming should be meaningful. Therefore, a package name should be short, concise, expressive, and, by convention, a single lowercase word.

Regarding what to export, the rule is pretty straightforward. We should minimize what should be exported as much as possible to reduce the coupling between packages and keep unnecessary exported elements hidden. If we are unsure whether to export an element or not, we should default to not exporting it. Later, if we discover that we need to export it, we can adjust our code. Let’s also keep in mind some exceptions, such as making fields exported so that a struct can be unmarshaled with encoding/json.

Organizing a project isn’t straightforward, but following these rules should help make it easier to maintain. However, remember that consistency is also vital to ease maintainability. Therefore, let’s make sure that we keep things as consistent as possible within a codebase.

???+ note

In 2023, the Go team has published an official guideline for organizing / structuring a Go project:

Creating utility packages (#13)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Naming is a critical piece of application design. Creating packages such as `common`, `util`, and `shared` doesn’t bring much value for the reader. Refactor such packages into meaningful and specific package names.

Also, bear in mind that naming a package after what it provides and not what it contains can be an efficient way to increase its expressiveness.

Ignoring package name collisions (#14)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To avoid naming collisions between variables and packages, leading to confusion or perhaps even bugs, use unique names for each one. If this isn’t feasible, use an import alias to change the qualifier to differentiate the package name from the variable name, or think of a better name.

Package collisions occur when a variable name collides with an existing package name, preventing the package from being reused. We should prevent variable name collisions to avoid ambiguity. If we face a collision, we should either find another meaningful name or use an import alias.

import (

fm "fmt" // Alias 'fm' for the 'fmt' package

myjson "encoding/json" // Alias 'myjson' for the 'encoding/json' package

)

Missing code documentation (#15)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To help clients and maintainers understand your code’s purpose, document exported elements.

Documentation is an important aspect of coding. It simplifies how clients can consume an API but can also help in maintaining a project. In Go, we should follow some rules to make our code idiomatic:

First, every exported element must be documented. Whether it is a structure, an interface, a function, or something else, if it’s exported, it must be documented. The convention is to add comments, starting with the name of the exported element.

As a convention, each comment should be a complete sentence that ends with punctuation. Also bear in mind that when we document a function (or a method), we should highlight what the function intends to do, not how it does it; this belongs to the core of a function and comments, not documentation. Furthermore, the documentation should ideally provide enough information that the consumer does not have to look at our code to understand how to use an exported element.

When it comes to documenting a variable or a constant, we might be interested in conveying two aspects: its purpose and its content. The former should live as code documentation to be useful for external clients. The latter, though, shouldn’t necessarily be public.

To help clients and maintainers understand a package’s scope, we should also document each package. The convention is to start the comment with // Package followed by the package name. The first line of a package comment should be concise. That’s because it will appear in the package. Then, we can provide all the information we need in the following lines.

Documenting our code shouldn’t be a constraint. We should take the opportunity to make sure it helps clients and maintainers to understand the purpose of our code.

Not using linters (#16)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To improve code quality and consistency, use linters and formatters.

A linter is an automatic tool to analyze code and catch errors. The scope of this section isn’t to give an exhaustive list of the existing linters; otherwise, it will become deprecated pretty quickly. But we should understand and remember why linters are essential for most Go projects.

However, if you’re not a regular user of linters, here is a list that you may want to use daily:

- https://golang.org/cmd/vet—A standard Go analyzer

- https://github.com/kisielk/errcheck—An error checker

- https://github.com/fzipp/gocyclo—A cyclomatic complexity analyzer

- https://github.com/jgautheron/goconst—A repeated string constants analyzer

Besides linters, we should also use code formatters to fix code style. Here is a list of some code formatters for you to try:

- https://golang.org/cmd/gofmt—A standard Go code formatter

- https://godoc.org/golang.org/x/tools/cmd/goimports—A standard Go imports formatter

Meanwhile, we should also look at golangci-lint (https://github.com/golangci/golangci-lint). It’s a linting tool that provides a facade on top of many useful linters and formatters. Also, it allows running the linters in parallel to improve analysis speed, which is quite handy.

Linters and formatters are a powerful way to improve the quality and consistency of our codebase. Let’s take the time to understand which one we should use and make sure we automate their execution (such as a CI or Git precommit hook).

Data Types

Creating confusion with octal literals (#17)

???+ info “TL;DR”

When reading existing code, bear in mind that integer literals starting with `0` are octal numbers. Also, to improve readability, make octal integers explicit by prefixing them with `0o`.

Octal numbers start with a 0 (e.g., 010 is equal to 8 in base 10). To improve readability and avoid potential mistakes for future code readers, we should make octal numbers explicit using the 0o prefix (e.g., 0o10).

We should also note the other integer literal representations:

- Binary—Uses a

0bor0Bprefix (for example,0b100is equal to 4 in base 10) - Hexadecimal—Uses an

0xor0Xprefix (for example,0xFis equal to 15 in base 10) - Imaginary—Uses an

isuffix (for example,3i)

We can also use an underscore character (_) as a separator for readability. For example, we can write 1 billion this way: 1_000_000_000. We can also use the underscore character with other representations (for example, 0b00_00_01).

Neglecting integer overflows (#18)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Because integer overflows and underflows are handled silently in Go, you can implement your own functions to catch them.

In Go, an integer overflow that can be detected at compile time generates a compilation error. For example,

var counter int32 = math.MaxInt32 + 1constant 2147483648 overflows int32However, at run time, an integer overflow or underflow is silent; this does not lead to an application panic. It is essential to keep this behavior in mind, because it can lead to sneaky bugs (for example, an integer increment or addition of positive integers that leads to a negative result).

Not understanding floating-points (#19)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Making floating-point comparisons within a given delta can ensure that your code is portable. When performing addition or subtraction, group the operations with a similar order of magnitude to favor accuracy. Also, perform multiplication and division before addition and subtraction.

In Go, there are two floating-point types (if we omit imaginary numbers): float32 and float64. The concept of a floating point was invented to solve the major problem with integers: their inability to represent fractional values. To avoid bad surprises, we need to know that floating-point arithmetic is an approximation of real arithmetic.

For that, we’ll look at a multiplication example:

var n float32 = 1.0001

fmt.Println(n * n)We may expect this code to print the result of 1.0001 * 1.0001 = 1.00020001, right? However, running it on most x86 processors prints 1.0002, instead.

Because Go’s float32 and float64 types are approximations, we have to bear a few rules in mind:

- When comparing two floating-point numbers, check that their difference is within an acceptable range.

- When performing additions or subtractions, group operations with a similar order of magnitude for better accuracy.

- To favor accuracy, if a sequence of operations requires addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division, perform the multiplication and division operations first.

Not understanding slice length and capacity (#20)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Understanding the difference between slice length and capacity should be part of a Go developer’s core knowledge. The slice length is the number of available elements in the slice, whereas the slice capacity is the number of elements in the backing array.

Read the full section here.

Inefficient slice initialization (#21)

???+ info “TL;DR”

When creating a slice, initialize it with a given length or capacity if its length is already known. This reduces the number of allocations and improves performance.

While initializing a slice using make, we can provide a length and an optional capacity. Forgetting to pass an appropriate value for both of these parameters when it makes sense is a widespread mistake. Indeed, it can lead to multiple copies and additional effort for the GC to clean the temporary backing arrays. Performance-wise, there’s no good reason not to give the Go runtime a helping hand.

Our options are to allocate a slice with either a given capacity or a given length. Of these two solutions, we have seen that the second tends to be slightly faster. But using a given capacity and append can be easier to implement and read in some contexts.

Being confused about nil vs. empty slice (#22)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To prevent common confusions such as when using the `encoding/json` or the `reflect` package, you need to understand the difference between nil and empty slices. Both are zero-length, zero-capacity slices, but only a nil slice doesn’t require allocation.

In Go, there is a distinction between nil and empty slices. A nil slice is equals to nil, whereas an empty slice has a length of zero. A nil slice is empty, but an empty slice isn’t necessarily nil. Meanwhile, a nil slice doesn’t require any allocation. We have seen throughout this section how to initialize a slice depending on the context by using

var s []stringif we aren’t sure about the final length and the slice can be empty[]string(nil)as syntactic sugar to create a nil and empty slicemake([]string, length)if the future length is known

The last option, []string{}, should be avoided if we initialize the slice without elements. Finally, let’s check whether the libraries we use make the distinctions between nil and empty slices to prevent unexpected behaviors.

Not properly checking if a slice is empty (#23)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To check if a slice doesn’t contain any element, check its length. This check works regardless of whether the slice is `nil` or empty. The same goes for maps. To design unambiguous APIs, you shouldn’t distinguish between nil and empty slices.

To determine whether a slice has elements, we can either do it by checking if the slice is nil or if its length is equal to 0. Checking the length is the best option to follow as it will cover both if the slice is empty or if the slice is nil.

Meanwhile, when designing interfaces, we should avoid distinguishing nil and empty slices, which leads to subtle programming errors. When returning slices, it should make neither a semantic nor a technical difference if we return a nil or empty slice. Both should mean the same thing for the callers. This principle is the same with maps. To check if a map is empty, check its length, not whether it’s nil.

Not making slice copies correctly (#24)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To copy one slice to another using the `copy` built-in function, remember that the number of copied elements corresponds to the minimum between the two slice’s lengths.

Copying elements from one slice to another is a reasonably frequent operation. When using copy, we must recall that the number of elements copied to the destination corresponds to the minimum between the two slices’ lengths. Also bear in mind that other alternatives exist to copy a slice, so we shouldn’t be surprised if we find them in a codebase.

Unexpected side effects using slice append (#25)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using copy or the full slice expression is a way to prevent `append` from creating conflicts if two different functions use slices backed by the same array. However, only a slice copy prevents memory leaks if you want to shrink a large slice.

When using slicing, we must remember that we can face a situation leading to unintended side effects. If the resulting slice has a length smaller than its capacity, append can mutate the original slice. If we want to restrict the range of possible side effects, we can use either a slice copy or the full slice expression, which prevents us from doing a copy.

???+ note

`s[low:high:max]` (full slice expression): This statement creates a slice similar to the one created with `s[low:high]`, except that the resulting slice’s capacity is equal to `max - low`.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

originalSlice := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Using the standard slice expression

newSlice := originalSlice[1:4]

newSlice = append(newSlice, 6)

fmt.Println("Original Slice:", originalSlice) // Original slice is modified

fmt.Println("New Slice:", newSlice)

// Resetting the original slice

originalSlice = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Using copy to prevent modification of the original slice

copiedSlice := make([]int, len(originalSlice))

copy(copiedSlice, originalSlice)

copiedSlice = append(copiedSlice[1:4], 6)

fmt.Println("Original Slice with Copy:", originalSlice) // Remains unchanged

fmt.Println("Copied Slice:", copiedSlice)

// Resetting the original slice again

originalSlice = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Using full slice expression

fullSliceExpr := originalSlice[1:4:4]

fullSliceExpr = append(fullSliceExpr, 6)

fmt.Println("Original Slice with Full Slice Expression:", originalSlice) // Remains unchanged

fmt.Println("Full Slice Expression:", fullSliceExpr)

}Slices and memory leaks (#26)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Working with a slice of pointers or structs with pointer fields, you can avoid memory leaks by marking as nil the elements excluded by a slicing operation.

Leaking capacity

Remember that slicing a large slice or array can lead to potential high memory consumption. The remaining space won’t be reclaimed by the GC, and we can keep a large backing array despite using only a few elements. Using a slice copy is the solution to prevent such a case.

The provided Go code demonstrates an important concept in managing memory efficiently when working with slices: avoiding “leaking capacity.” Let’s break down the key points and the code step by step:

Leaking Capacity Explained

-

Slicing Large Arrays or Slices: When you create a slice from a larger array or slice, the new slice retains a reference to the original array’s memory block. This means that even if you’re using only a small part of the array, the entire memory block remains allocated.

-

Garbage Collection (GC) and Unused Memory: In Go, the garbage collector can only reclaim memory that is no longer referenced. If you have a small slice that references a large array, the entire array cannot be garbage collected, even if you’re only using a small portion of it.

-

Memory Consumption: As a result, you might end up consuming more memory than necessary, which is known as “leaking capacity.”

Solution: Using a Slice Copy

To prevent leaking capacity, you can create a copy of the slice with only the elements you need. This way, the new slice does not reference the original large array, allowing unused memory to be reclaimed by the GC.

Code Explanation

In your provided code, there are two functions getMessageType and getMessageTypeWithCopy that demonstrate the difference between slicing and copying:

func getMessageType(msg []byte) []byte {

return msg[:5]

}

func getMessageTypeWithCopy(msg []byte) []byte {

msgType := make([]byte, 5)

copy(msgType, msg)

return msgType

}-

getMessageTypereturns the first 5 bytes ofmsgby slicing. However, this returned slice still references the original largemsgslice. Ifmsgis large, this keeps a large memory block allocated even though only a small part is being used. -

getMessageTypeWithCopy, on the other hand, creates a new slicemsgTypeof the required length (5 bytes) and copies the relevant data into it. This new slice does not reference the original largemsgslice, allowing the GC to reclaim the memory used bymsgif it’s no longer needed elsewhere.

The receiveMessage function simulates receiving a large message (1,000,000 bytes). In a continuous processing loop like consumeMessages, using getMessageType could lead to high memory consumption because each message slice retains a reference to the entire large array. In contrast, getMessageTypeWithCopy avoids this issue by using only the necessary amount of memory.

Finally, printAlloc is a utility function to print the current memory allocation, useful for monitoring memory usage during the program’s execution.

Slice and pointers

When we use the slicing operation with pointers or structs with pointer fields, we need to know that the GC won’t reclaim these elements. In that case, the two options are to either perform a copy or explicitly mark the remaining elements or their fields to nil.

When dealing with slices of pointers or structs containing pointer fields in Go, it’s important to understand how garbage collection (GC) interacts with these structures. The key issue is that as long as the slice holds references (pointers) to objects, the GC cannot reclaim the memory used by these objects, even if they are no longer needed. This can lead to memory leaks if not handled properly.

Options to Prevent Memory Leaks

-

Performing a Copy: Create a new slice and copy only the needed elements. This way, the original slice can be garbage collected if there are no other references to it.

-

Setting Unneeded Elements to

nil: Explicitly set the pointers of unneeded elements tonilin the original slice. This breaks the reference, allowing the GC to reclaim the memory used by those objects.

Example Code

Let’s illustrate both approaches with an example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

)

type Data struct {

// Assume this struct has pointer fields

}

func main() {

// Create a slice of pointers

originalSlice := make([]*Data, 10)

for i := range originalSlice {

originalSlice[i] = &Data{}

}

// Option 1: Perform a copy

copiedSlice := make([]*Data, 5)

copy(copiedSlice, originalSlice[:5])

// Option 2: Set unneeded elements to nil

for i := 5; i < len(originalSlice); i++ {

originalSlice[i] = nil

}

// At this point, the second half of originalSlice can be garbage collected

// The copiedSlice contains the first half of the elements

printMemoryUsage()

}

func printMemoryUsage() {

var m runtime.MemStats

runtime.ReadMemStats(&m)

fmt.Printf("Memory Usage: %d KB\n", m.Alloc/1024)

}In this code:

- We create a slice

originalSliceof pointers toDatastructs. - We then demonstrate two options:

- Perform a Copy: We create

copiedSlice, a new slice, and copy the first half oforiginalSliceinto it. This isolatescopiedSlicefromoriginalSlice, allowingoriginalSliceto be garbage collected if there are no other references. - Set to

nil: We loop through the second half oforiginalSliceand set each element tonil. This breaks the references to theDataobjects in that part of the slice, allowing them to be garbage collected.

- Perform a Copy: We create

- Finally, we print the current memory usage to observe the effect of our memory management.

By following these approaches, you can ensure that unused objects in a slice are eligible for garbage collection, thus preventing memory leaks in your Go applications.

Inefficient map initialization (#27)

???+ info “TL;DR”

When creating a map, initialize it with a given length if its length is already known. This reduces the number of allocations and improves performance.

A map provides an unordered collection of key-value pairs in which all the keys are distinct. In Go, a map is based on the hash table data structure. Internally, a hash table is an array of buckets, and each bucket is a pointer to an array of key-value pairs.

If we know up front the number of elements a map will contain, we should create it by providing an initial size. Doing this avoids potential map growth, which is quite heavy computation-wise because it requires reallocating enough space and rebalancing all the elements.

Maps and memory leaks (#28)

???+ info “TL;DR”

A map can always grow in memory, but it never shrinks. Hence, if it leads to some memory issues, you can try different options, such as forcing Go to recreate the map or using pointers.

Read the full section here.

Comparing values incorrectly (#29)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To compare types in Go, you can use the == and != operators if two types are comparable: Booleans, numerals, strings, pointers, channels, and structs are composed entirely of comparable types. Otherwise, you can either use `reflect.DeepEqual` and pay the price of reflection or use custom implementations and libraries.

It’s essential to understand how to use == and != to make comparisons effectively. We can use these operators on operands that are comparable:

- Booleans—Compare whether two Booleans are equal.

- Numerics (int, float, and complex types)—Compare whether two numerics are equal.

- Strings—Compare whether two strings are equal.

- Channels—Compare whether two channels were created by the same call to make or if both are nil.

- Interfaces—Compare whether two interfaces have identical dynamic types and equal dynamic values or if both are nil.

- Pointers—Compare whether two pointers point to the same value in memory or if both are nil.

- Structs and arrays—Compare whether they are composed of similar types.

???+ note

We can also use the `?`, `>=`, `<`, and `>` operators with numeric types to compare values and with strings to compare their lexical order.

If operands are not comparable (e.g., slices and maps), we have to use other options such as reflection. Reflection is a form of metaprogramming, and it refers to the ability of an application to introspect and modify its structure and behavior. For example, in Go, we can use reflect.DeepEqual. This function reports whether two elements are deeply equal by recursively traversing two values. The elements it accepts are basic types plus arrays, structs, slices, maps, pointers, interfaces, and functions. Yet, the main catch is the performance penalty.

If performance is crucial at run time, implementing our custom method might be the best solution.

One additional note: we must remember that the standard library has some existing comparison methods. For example, we can use the optimized bytes.Compare function to compare two slices of bytes. Before implementing a custom method, we need to make sure we don’t reinvent the wheel.

Control Structures

Ignoring that elements are copied in range loops (#30)

???+ info “TL;DR”

The value element in a `range` loop is a copy. Therefore, to mutate a struct, for example, access it via its index or via a classic `for` loop (unless the element or the field you want to modify is a pointer).

A range loop allows iterating over different data structures:

- String

- Array

- Pointer to an array

- Slice

- Map

- Receiving channel

Compared to a classic for loop, a range loop is a convenient way to iterate over all the elements of one of these data structures, thanks to its concise syntax.

Yet, we should remember that the value element in a range loop is a copy. Therefore, if the value is a struct we need to mutate, we will only update the copy, not the element itself, unless the value or field we modify is a pointer. The favored options are to access the element via the index using a range loop or a classic for loop.

Ignoring how arguments are evaluated in range loops (channels and arrays) (#31)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Understanding that the expression passed to the `range` operator is evaluated only once before the beginning of the loop can help you avoid common mistakes such as inefficient assignment in channel or slice iteration.

The range loop evaluates the provided expression only once, before the beginning of the loop, by doing a copy (regardless of the type). We should remember this behavior to avoid common mistakes that might, for example, lead us to access the wrong element. For example:

a := [3]int{0, 1, 2}

for i, v := range a {

a[2] = 10

if i == 2 {

fmt.Println(v)

}

}This code updates the last index to 10. However, if we run this code, it does not print 10; it prints 2.

Ignoring the impacts of using pointer elements in range loops (#32)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using a local variable or accessing an element using an index, you can prevent mistakes while copying pointers inside a loop.

When iterating over a data structure using a range loop, we must recall that all the values are assigned to a unique variable with a single unique address. Therefore, if we store a pointer referencing this variable during each iteration, we will end up in a situation where we store the same pointer referencing the same element: the latest one. We can overcome this issue by forcing the creation of a local variable in the loop’s scope or creating a pointer referencing a slice element via its index. Both solutions are fine.

Making wrong assumptions during map iterations (ordering and map insert during iteration) (#33)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To ensure predictable outputs when using maps, remember that a map data structure:

- Doesn’t order the data by keys

- Doesn’t preserve the insertion order

- Doesn’t have a deterministic iteration order

- Doesn’t guarantee that an element added during an iteration will be produced during this iteration

Ignoring how the break statement works (#34)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using `break` or `continue` with a label enforces breaking a specific statement. This can be helpful with `switch` or `select` statements inside loops.

A break statement is commonly used to terminate the execution of a loop. When loops are used in conjunction with switch or select, developers frequently make the mistake of breaking the wrong statement. For example:

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Printf("%d ", i)

switch i {

default:

case 2:

break

}

}The break statement doesn’t terminate the for loop: it terminates the switch statement, instead. Hence, instead of iterating from 0 to 2, this code iterates from 0 to 4: 0 1 2 3 4.

One essential rule to keep in mind is that a break statement terminates the execution of the innermost for, switch, or select statement. In the previous example, it terminates the switch statement.

To break the loop instead of the switch statement, the most idiomatic way is to use a label:

loop:

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Printf("%d ", i)

switch i {

default:

case 2:

break loop

}

}Here, we associate the loop label with the for loop. Then, because we provide the loop label to the break statement, it breaks the loop, not the switch. Therefore, this new version will print 0 1 2, as we expected.

Using defer inside a loop (#35)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Extracting loop logic inside a function leads to executing a `defer` statement at the end of each iteration.

The defer statement delays a call’s execution until the surrounding function returns. It’s mainly used to reduce boilerplate code. For example, if a resource has to be closed eventually, we can use defer to avoid repeating the closure calls before every single return.

One common mistake with defer is to forget that it schedules a function call when the surrounding function returns. For example:

func readFiles(ch <-chan string) error {

for path := range ch {

file, err := os.Open(path)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer file.Close()

// Do something with file

}

return nil

}The defer calls are executed not during each loop iteration but when the readFiles function returns. If readFiles doesn’t return, the file descriptors will be kept open forever, causing leaks.

One common option to fix this problem is to create a surrounding function after defer, called during each iteration:

func readFiles(ch <-chan string) error {

for path := range ch {

if err := readFile(path); err != nil {

return err

}

}

return nil

}

func readFile(path string) error {

file, err := os.Open(path)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer file.Close()

// Do something with file

return nil

}Another solution is to make the readFile function a closure but intrinsically, this remains the same solution: adding another surrounding function to execute the defer calls during each iteration.

Strings

Not understanding the concept of rune (#36)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Understanding that a rune corresponds to the concept of a Unicode code point and that it can be composed of multiple bytes should be part of the Go developer’s core knowledge to work accurately with strings.

As runes are everywhere in Go, it’s important to understand the following:

- A charset is a set of characters, whereas an encoding describes how to translate a charset into binary.

- In Go, a string references an immutable slice of arbitrary bytes.

- Go source code is encoded using UTF-8. Hence, all string literals are UTF-8 strings. But because a string can contain arbitrary bytes, if it’s obtained from somewhere else (not the source code), it isn’t guaranteed to be based on the UTF-8 encoding.

- A

runecorresponds to the concept of a Unicode code point, meaning an item represented by a single value. - Using UTF-8, a Unicode code point can be encoded into 1 to 4 bytes.

- Using

len()on a string in Go returns the number of bytes, not the number of runes.

Inaccurate string iteration (#37)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Iterating on a string with the `range` operator iterates on the runes with the index corresponding to the starting index of the rune’s byte sequence. To access a specific rune index (such as the third rune), convert the string into a `[]rune`.

Iterating on a string is a common operation for developers. Perhaps we want to perform an operation for each rune in the string or implement a custom function to search for a specific substring. In both cases, we have to iterate on the different runes of a string. But it’s easy to get confused about how iteration works.

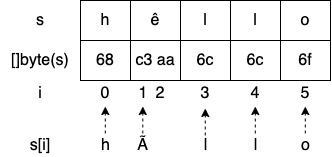

For example, consider the following example:

s := "hêllo"

for i := range s {

fmt.Printf("position %d: %c\n", i, s[i])

}

fmt.Printf("len=%d\n", len(s))position 0: h

position 1: Ã

position 3: l

position 4: l

position 5: o

len=6

Let’s highlight three points that might be confusing:

- The second rune is à in the output instead of ê.

- We jumped from position 1 to position 3: what is at position 2?

- len returns a count of 6, whereas s contains only 5 runes.

Let’s start with the last observation. We already mentioned that len returns the number of bytes in a string, not the number of runes. Because we assigned a string literal to s, s is a UTF-8 string. Meanwhile, the special character “ê” isn’t encoded in a single byte; it requires 2 bytes. Therefore, calling len(s) returns 6.

Meanwhile, in the previous example, we have to understand that we don’t iterate over each rune; instead, we iterate over each starting index of a rune:

Printing

Printing s[i] doesn’t print the ith rune; it prints the UTF-8 representation of the byte at index i. Hence, we printed “hÃllo” instead of “hêllo”.

If we want to print all the different runes, we can either use the value element of the range operator:

s := "hêllo"

for i, r := range s {

fmt.Printf("position %d: %c\n", i, r)

}Or, we can convert the string into a slice of runes and iterate over it:

s := "hêllo"

runes := []rune(s)

for i, r := range runes {

fmt.Printf("position %d: %c\n", i, r)

}Note that this solution introduces a run-time overhead compared to the previous one. Indeed, converting a string into a slice of runes requires allocating an additional slice and converting the bytes into runes: an O(n) time complexity with n the number of bytes in the string. Therefore, if we want to iterate over all the runes, we should use the first solution.

However, if we want to access the ith rune of a string with the first option, we don’t have access to the rune index; rather, we know the starting index of a rune in the byte sequence.

s := "hêllo"

r := []rune(s)[4]

fmt.Printf("%c\n", r) // oMisusing trim functions (#38)

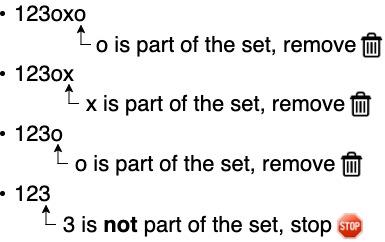

???+ info “TL;DR”

`strings.TrimRight`/`strings.TrimLeft` removes all the trailing/leading runes contained in a given set, whereas `strings.TrimSuffix`/`strings.TrimPrefix` returns a string without a provided suffix/prefix.

For example:

fmt.Println(strings.TrimRight("123oxo", "xo"))The example prints 123:

Conversely, strings.TrimLeft removes all the leading runes contained in a set.

On the other side, strings.TrimSuffix / strings.TrimPrefix returns a string without the provided trailing suffix / prefix.

Under-optimized strings concatenation (#39)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Concatenating a list of strings should be done with `strings.Builder` to prevent allocating a new string during each iteration.

Let’s consider a concat function that concatenates all the string elements of a slice using the += operator:

func concat(values []string) string {

s := ""

for _, value := range values {

s += value

}

return s

}During each iteration, the += operator concatenates s with the value string. At first sight, this function may not look wrong. But with this implementation, we forget one of the core characteristics of a string: its immutability. Therefore, each iteration doesn’t update s; it reallocates a new string in memory, which significantly impacts the performance of this function.

Fortunately, there is a solution to deal with this problem, using strings.Builder:

func concat(values []string) string {

sb := strings.Builder{}

for _, value := range values {

_, _ = sb.WriteString(value)

}

return sb.String()

}During each iteration, we constructed the resulting string by calling the WriteString method that appends the content of value to its internal buffer, hence minimizing memory copying.

???+ note

`WriteString` returns an error as the second output, but we purposely ignore it. Indeed, this method will never return a non-nil error. So what’s the purpose of this method returning an error as part of its signature? `strings.Builder` implements the `io.StringWriter` interface, which contains a single method: `WriteString(s string) (n int, err error)`. Hence, to comply with this interface, `WriteString` must return an error.

Internally, strings.Builder holds a byte slice. Each call to WriteString results in a call to append on this slice. There are two impacts. First, this struct shouldn’t be used concurrently, as the calls to append would lead to race conditions. The second impact is something that we saw in mistake #21, “Inefficient slice initialization”: if the future length of a slice is already known, we should preallocate it. For that purpose, strings.Builder exposes a method Grow(n int) to guarantee space for another n bytes:

func concat(values []string) string {

total := 0

for i := 0; i < len(values); i++ {

total += len(values[i])

}

sb := strings.Builder{}

sb.Grow(total) (2)

for _, value := range values {

_, _ = sb.WriteString(value)

}

return sb.String()

}Let’s run a benchmark to compare the three versions (v1 using +=; v2 using strings.Builder{} without preallocation; and v3 using strings.Builder{} with preallocation). The input slice contains 1,000 strings, and each string contains 1,000 bytes:

BenchmarkConcatV1-4 16 72291485 ns/op

BenchmarkConcatV2-4 1188 878962 ns/op

BenchmarkConcatV3-4 5922 190340 ns/op

As we can see, the latest version is by far the most efficient: 99% faster than v1 and 78% faster than v2.

strings.Builder is the recommended solution to concatenate a list of strings. Usually, this solution should be used within a loop. Indeed, if we just have to concatenate a few strings (such as a name and a surname), using strings.Builder is not recommended as doing so will make the code a bit less readable than using the += operator or fmt.Sprintf.

Useless string conversions (#40)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Remembering that the `bytes` package offers the same operations as the `strings` package can help avoid extra byte/string conversions.

When choosing to work with a string or a []byte, most programmers tend to favor strings for convenience. But most I/O is actually done with []byte. For example, io.Reader, io.Writer, and io.ReadAll work with []byte, not strings.

When we’re wondering whether we should work with strings or []byte, let’s recall that working with []byte isn’t necessarily less convenient. Indeed, all the exported functions of the strings package also have alternatives in the bytes package: Split, Count, Contains, Index, and so on. Hence, whether we’re doing I/O or not, we should first check whether we could implement a whole workflow using bytes instead of strings and avoid the price of additional conversions.

Substring and memory leaks (#41)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using copies instead of substrings can prevent memory leaks, as the string returned by a substring operation will be backed by the same byte array.

In mistake #26, “Slices and memory leaks,” we saw how slicing a slice or array may lead to memory leak situations. This principle also applies to string and substring operations.

We need to keep two things in mind while using the substring operation in Go. First, the interval provided is based on the number of bytes, not the number of runes. Second, a substring operation may lead to a memory leak as the resulting substring will share the same backing array as the initial string. The solutions to prevent this case from happening are to perform a string copy manually or to use strings.Clone from Go 1.18.

Functions and Methods

Not knowing which type of receiver to use (#42)

???+ info “TL;DR”

The decision whether to use a value or a pointer receiver should be made based on factors such as the type, whether it has to be mutated, whether it contains a field that can’t be copied, and how large the object is. When in doubt, use a pointer receiver.

Choosing between value and pointer receivers isn’t always straightforward. Let’s discuss some of the conditions to help us choose.

A receiver must be a pointer

-

If the method needs to mutate the receiver. This rule is also valid if the receiver is a slice and a method needs to append elements:

type slice []int func (s *slice) add(element int) { *s = append(*s, element) } -

If the method receiver contains a field that cannot be copied: for example, a type part of the sync package (see #74, “Copying a sync type”).

A receiver should be a pointer

- If the receiver is a large object. Using a pointer can make the call more efficient, as doing so prevents making an extensive copy. When in doubt about how large is large, benchmarking can be the solution; it’s pretty much impossible to state a specific size, because it depends on many factors.

A receiver must be a value

- If we have to enforce a receiver’s immutability.

- If the receiver is a map, function, or channel. Otherwise, a compilation error occurs.

A receiver should be a value

- If the receiver is a slice that doesn’t have to be mutated.

- If the receiver is a small array or struct that is naturally a value type without mutable fields, such as

time.Time. - If the receiver is a basic type such as

int,float64, orstring.

Of course, it’s impossible to be exhaustive, as there will always be edge cases, but this section’s goal was to provide guidance to cover most cases. By default, we can choose to go with a value receiver unless there’s a good reason not to do so. In doubt, we should use a pointer receiver.

Never using named result parameters (#43)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using named result parameters can be an efficient way to improve the readability of a function/method, especially if multiple result parameters have the same type. In some cases, this approach can also be convenient because named result parameters are initialized to their zero value. But be cautious about potential side effects.

When we return parameters in a function or a method, we can attach names to these parameters and use them as regular variables. When a result parameter is named, it’s initialized to its zero value when the function/method begins. With named result parameters, we can also call a naked return statement (without arguments). In that case, the current values of the result parameters are used as the returned values.

Here’s an example that uses a named result parameter b:

func f(a int) (b int) {

b = a

return

}In this example, we attach a name to the result parameter: b. When we call return without arguments, it returns the current value of b.

In some cases, named result parameters can also increase readability: for example, if two parameters have the same type. In other cases, they can also be used for convenience. Therefore, we should use named result parameters sparingly when there’s a clear benefit.

Unintended side effects with named result parameters (#44)

???+ info “TL;DR”

See [#43](#never-using-named-result-parameters-43).

We mentioned why named result parameters can be useful in some situations. But as these result parameters are initialized to their zero value, using them can sometimes lead to subtle bugs if we’re not careful enough. For example, can you spot what’s wrong with this code?

func (l loc) getCoordinates(ctx context.Context, address string) (

lat, lng float32, err error) {

isValid := l.validateAddress(address) (1)

if !isValid {

return 0, 0, errors.New("invalid address")

}

if ctx.Err() != nil { (2)

return 0, 0, err

}

// Get and return coordinates

}The error might not be obvious at first glance. Here, the error returned in the if ctx.Err() != nil scope is err. But we haven’t assigned any value to the err variable. It’s still assigned to the zero value of an error type: nil. Hence, this code will always return a nil error.

When using named result parameters, we must recall that each parameter is initialized to its zero value. As we have seen in this section, this can lead to subtle bugs that aren’t always straightforward to spot while reading code. Therefore, let’s remain cautious when using named result parameters, to avoid potential side effects.

Returning a nil receiver (#45)

???+ info “TL;DR”

When returning an interface, be cautious about not returning a nil pointer but an explicit nil value. Otherwise, unintended consequences may occur and the caller will receive a non-nil value.

Using a filename as a function input (#46)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Designing functions to receive `io.Reader` types instead of filenames improves the reusability of a function and makes testing easier.

Accepting a filename as a function input to read from a file should, in most cases, be considered a code smell (except in specific functions such as os.Open). Indeed, it makes unit tests more complex because we may have to create multiple files. It also reduces the reusability of a function (although not all functions are meant to be reused). Using the io.Reader interface abstracts the data source. Regardless of whether the input is a file, a string, an HTTP request, or a gRPC request, the implementation can be reused and easily tested.

Ignoring how defer arguments and receivers are evaluated (argument evaluation, pointer, and value receivers) (#47)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Passing a pointer to a `defer` function and wrapping a call inside a closure are two possible solutions to overcome the immediate evaluation of arguments and receivers.

In a defer function the arguments are evaluated right away, not once the surrounding function returns. For example, in this code, we always call notify and incrementCounter with the same status: an empty string.

const (

StatusSuccess = "success"

StatusErrorFoo = "error_foo"

StatusErrorBar = "error_bar"

)

func f() error {

var status string

defer notify(status)

defer incrementCounter(status)

if err := foo(); err != nil {

status = StatusErrorFoo

return err

}

if err := bar(); err != nil {

status = StatusErrorBar

return err

}

status = StatusSuccess <5>

return nil

}Indeed, we call notify(status) and incrementCounter(status) as defer functions. Therefore, Go will delay these calls to be executed once f returns with the current value of status at the stage we used defer, hence passing an empty string.

Two leading options if we want to keep using defer.

The first solution is to pass a string pointer:

func f() error {

var status string

defer notify(&status)

defer incrementCounter(&status)

// The rest of the function unchanged

}Using defer evaluates the arguments right away: here, the address of status. Yes, status itself is modified throughout the function, but its address remains constant, regardless of the assignments. Hence, if notify or incrementCounter uses the value referenced by the string pointer, it will work as expected. But this solution requires changing the signature of the two functions, which may not always be possible.

There’s another solution: calling a closure (an anonymous function value that references variables from outside its body) as a defer statement:

func f() error {

var status string

defer func() {

notify(status)

incrementCounter(status)

}()

// The rest of the function unchanged

}Here, we wrap the calls to both notify and incrementCounter within a closure. This closure references the status variable from outside its body. Therefore, status is evaluated once the closure is executed, not when we call defer. This solution also works and doesn’t require notify and incrementCounter to change their signature.

Let’s also note this behavior applies with method receiver: the receiver is evaluated immediately.

Error Management

Panicking (#48)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Using `panic` is an option to deal with errors in Go. However, it should only be used sparingly in unrecoverable conditions: for example, to signal a programmer error or when you fail to load a mandatory dependency.

In Go, panic is a built-in function that stops the ordinary flow:

func main() {

fmt.Println("a")

panic("foo")

fmt.Println("b")

}This code prints a and then stops before printing b:

a

panic: foo

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.main()

main.go:7 +0xb3

Panicking in Go should be used sparingly. There are two prominent cases, one to signal a programmer error (e.g., sql.Register that panics if the driver is nil or has already been register) and another where our application fails to create a mandatory dependency. Hence, exceptional conditions that lead us to stop the application. In most other cases, error management should be done with a function that returns a proper error type as the last return argument.

Ignoring when to wrap an error (#49)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Wrapping an error allows you to mark an error and/or provide additional context. However, error wrapping creates potential coupling as it makes the source error available for the caller. If you want to prevent that, don’t use error wrapping.

Since Go 1.13, the %w directive allows us to wrap errors conveniently. Error wrapping is about wrapping or packing an error inside a wrapper container that also makes the source error available. In general, the two main use cases for error wrapping are the following:

- Adding additional context to an error

- Marking an error as a specific error

When handling an error, we can decide to wrap it. Wrapping is about adding additional context to an error and/or marking an error as a specific type. If we need to mark an error, we should create a custom error type. However, if we just want to add extra context, we should use fmt.Errorf with the %w directive as it doesn’t require creating a new error type. Yet, error wrapping creates potential coupling as it makes the source error available for the caller. If we want to prevent it, we shouldn’t use error wrapping but error transformation, for example, using fmt.Errorf with the %v directive.

Comparing an error type inaccurately (#50)

???+ info “TL;DR”

If you use Go 1.13 error wrapping with the `%w` directive and `fmt.Errorf`, comparing an error against a type has to be done using `errors.As`. Otherwise, if the returned error you want to check is wrapped, it will fail the checks.

Comparing an error value inaccurately (#51)

???+ info “TL;DR”

If you use Go 1.13 error wrapping with the `%w` directive and `fmt.Errorf`, comparing an error against or a value has to be done using `errors.As`. Otherwise, if the returned error you want to check is wrapped, it will fail the checks.

A sentinel error is an error defined as a global variable:

import "errors"

var ErrFoo = errors.New("foo")In general, the convention is to start with Err followed by the error type: here, ErrFoo. A sentinel error conveys an expected error, an error that clients will expect to check. As general guidelines:

- Expected errors should be designed as error values (sentinel errors):

var ErrFoo = errors.New("foo"). - Unexpected errors should be designed as error types:

type BarError struct { ... }, withBarErrorimplementing theerrorinterface.

If we use error wrapping in our application with the %w directive and fmt.Errorf, checking an error against a specific value should be done using errors.Is instead of ==. Thus, even if the sentinel error is wrapped, errors.Is can recursively unwrap it and compare each error in the chain against the provided value.

Handling an error twice (#52)

???+ info “TL;DR”

In most situations, an error should be handled only once. Logging an error is handling an error. Therefore, you have to choose between logging or returning an error. In many cases, error wrapping is the solution as it allows you to provide additional context to an error and return the source error.

Handling an error multiple times is a mistake made frequently by developers, not specifically in Go. This can cause situations where the same error is logged multiple times make debugging harder.

Let’s remind us that handling an error should be done only once. Logging an error is handling an error. Hence, we should either log or return an error. By doing this, we simplify our code and gain better insights into the error situation. Using error wrapping is the most convenient approach as it allows us to propagate the source error and add context to an error.

Not handling an error (#53)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Ignoring an error, whether during a function call or in a `defer` function, should be done explicitly using the blank identifier. Otherwise, future readers may be confused about whether it was intentional or a miss.

Not handling defer errors (#54)

???+ info “TL;DR”

In many cases, you shouldn’t ignore an error returned by a `defer` function. Either handle it directly or propagate it to the caller, depending on the context. If you want to ignore it, use the blank identifier.

Consider the following code:

func f() {

// ...

notify() // Error handling is omitted

}

func notify() error {

// ...

}From a maintainability perspective, the code can lead to some issues. Let’s consider a new reader looking at it. This reader notices that notify returns an error but that the error isn’t handled by the parent function. How can they guess whether or not handling the error was intentional? How can they know whether the previous developer forgot to handle it or did it purposely?

For these reasons, when we want to ignore an error, there’s only one way to do it, using the blank identifier (_):

_ = notifyIn terms of compilation and run time, this approach doesn’t change anything compared to the first piece of code. But this new version makes explicit that we aren’t interested in the error. Also, we can add a comment that indicates the rationale for why an error is ignored:

// At-most once delivery.

// Hence, it's accepted to miss some of them in case of errors.

_ = notify()Concurrency: Foundations

Mixing up concurrency and parallelism (#55)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Understanding the fundamental differences between concurrency and parallelism is a cornerstone of the Go developer’s knowledge. Concurrency is about structure, whereas parallelism is about execution.

Concurrency and parallelism are not the same:

- Concurrency is about structure. We can change a sequential implementation into a concurrent one by introducing different steps that separate concurrent goroutines can tackle.

- Meanwhile, parallelism is about execution. We can use parallism at the steps level by adding more parallel goroutines.

In summary, concurrency provides a structure to solve a problem with parts that may be parallelized. Therefore, concurrency enables parallelism.

Thinking concurrency is always faster (#56)

???+ info “TL;DR”

To be a proficient developer, you must acknowledge that concurrency isn’t always faster. Solutions involving parallelization of minimal workloads may not necessarily be faster than a sequential implementation. Benchmarking sequential versus concurrent solutions should be the way to validate assumptions.

Read the full section here.

Being puzzled about when to use channels or mutexes (#57)

???+ info “TL;DR”

Being aware of goroutine interactions can also be helpful when deciding between channels and mutexes. In general, parallel goroutines require synchronization and hence mutexes. Conversely, concurrent goroutines generally require coordination and orchestration and hence channels.

Given a concurrency problem, it may not always be clear whether we can implement a solution using channels or mutexes. Because Go promotes sharing memory by communication, one mistake could be to always force the use of channels, regardless of the use case. However, we should see the two options as complementary.

When should we use channels or mutexes? We will use the example in the next figure as a backbone. Our example has three different goroutines with specific relationships:

- G1 and G2 are parallel goroutines. They may be two goroutines executing the same function that keeps receiving messages from a channel, or perhaps two goroutines executing the same HTTP handler at the same time.